Don’t start at the finish

No matter how good your work is overall, the end result will never be better than the weakest link. Only by optimising each and every layer can you ensure that the final outcome will be an absolute long-term success.

Any quality process begins with a clear promise and ends with consistent, proven delivery. A process consists of design, plan, execution and, often, quality check. Each of these steps are equally important, although the quality control is frequently not necessary if the first three are carried out thoroughly and completely.

Quality management and assurance can take countless forms and have undergone many developments from the early days of modern production, with the biggest leaps seen in the post-war years.

The US engineer, statistician and management consultant W. Edwards Deming pretty much established this topic. Although a lot of his thought has since been finetuned, he remains the major authority on this issue… That may just be my opinion but I’m sticking to it!

I have previously written that, if you don’t know where you’re going, you’ll never know if you got there (https://lnkd.in/dTnsyg8). But in addition to knowing your destination, it also helps if you know how and when you are going to get there. In the case of a painting process, a yard should start with a specification from the material manufacturer. This should state the required DFTs, overcoating times and application conditions, as well as any other important recommendations.

The owners will also hopefully have an idea of the colour they expect. Things can get tricky when we talk about superyacht finish – the owner may or may not have specific expectations on how the vessel is faired and the gloss & orange peel levels acceptable. These ‘soft’ goals depend on factors outside a paint supplier’s data sheets. They are different from the specified technical performance of the product that needs to be met. Consider tank coating. This generally involves a required minimum DFT. Whether the finish applied is textured or not has a vanishingly small effect on the performance of the tank. Likewise, with the topcoat, the paint may be applied very smoothly or very roughly. Technically this will make very little difference in terms of resistance to sun and moisture. Aesthetics is another thing entirely, however.

To ensure compliance with any paint supplier recommendations, an inspection & testing plan or paint inspection plan should ideally be made before the project begins. This will formalise the procedures to be used in QA/QC throughout the painting process. The inspection plan should outline every layer in the process, stating all the information relevant for the product. This is very specific to each layer. The inspection plan should detail the following steps:

- Location of product to be applied;

- The exact product to be applied;

- Surface preparation and cleanliness before application;

- Application conditions (maximum and minimum temperature of substrate and air, humidity limits);

- Nominal film thickness with maximum and minimums;

- The methods to be used to test these criteria. This should include not only the test method but also the number of tests;

- The pass/fail criteria – for example, which percentage outside the agreed numbers is acceptable?

- Actions to be taken to rectify any issues and carry out QC again.

Do you want to be forced to accept this?

Or this?

For day-to-day QA, the paint contractor should confirm compliance with the requirements of ambient conditions and record the batch numbers used.

In any plan, it should be clear who will sign off on the stages within specification. There is a reason why they call them release forms – they signify that the process has been released for the following stage, like the next coat, or that the process is completed to the contractual requirements and that it is finished as far as the painter is concerned. These stages are often further defined as ‘witness’ or ‘hold’ points. A ‘witness point’ is where the relevant parties are invited to confirm the testing, but attendance is not mandatory, while a ‘hold point’ is where the relevant parties will all observe and sign-off before further step.

A typical example is the application of various layers of filler. The usual test procedure would perhaps just be a visual check to confirm that the surface is sanded, cured and free of dust and any large air pockets. While the owner’s representative may wish to check this randomly, they may also feel that they trust the yard and painter to do this. However, the owner’s representative may feel that confirming that the surface has been prepared properly for the topcoat is more critical and thus warrants personal attendance and sign-off before painting. It is easy to imagine issues that might arise if this personal check does not take place. If the paint has been applied and there are defects that need to be repaired, there might be a huge discussion on cause and responsibility, and nobody needs that.

So, which controls should be in the inspection plan? This is normally based on the fundamental requirements of the products used. Next to these, it is up to the yard (new build or refit) and the owner to determine what needs to be carried out and how. It is important that these requirements be part of the original tender documents and final work order. The clichés about managing expectations are based on the observation that there is often a mismatch if these elements have not been agreed clearly enough in the contract. Major points of concern depend on the layer, coating, substrate and location.

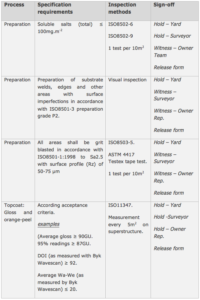

Table 1: Some typical inspections by area

The test method should be chosen among all these possible tests and should conform to industry standards. The one most relevant to yachts is the ISO11347, which defines many test methods for use with exterior finish. There are also many other common standards, such as the ISO, SSPC or ASTM, which are specific to particular tests. However, these only describe and define the test procedure, but do not specify the pass/fail. The latter is defined by the supplier recommendations or the yard and customer agreement. For example, ISO8502-6 explains how to test for soluble salts, but the specific level allowed is recommended by the supplier. To confuse things further, recommendations for a water tank are very different from what is allowed in the superstructure interiors. This is why is it essential to agree tolerance levels before beginning work.

Do you want this paint in your grey water tank?

Table 2: Example inspection plan

Note that, while there are standards such as ISO11347 that suggest measurement frequency, as I have discussed previously there is no reason to not allow further testing.

Likewise, a supplier may recommend a certain level of soluble salt. However, a yard may decide based on previous experience that this level should be lower. Even so, I repeat that these should be discussed and agreed before any work begins as to prevent mismatches in expectations. Remember that, while the yard may have sold the contract, it may still have to buy in the painting subcontractor to abide by the agreed limits.

Wave scan readings take the subjective element out of topcoat evaluation

All these details must be recorded and distributed to those concerned (as agreed in any test plan). This paperwork is not onerous and is essential to ensure that all control steps are followed.

CCS has spent a great deal of time and effort developing a digital recording system which documents all these steps, thus helping to reduce stress and paperwork. The system begins with all the relevant documentation digitally pre-entered. It logs all sign-offs and any outstanding issues, this generating a constantly up-to-date snag list to ensure that, at the end of the contract, all work has been performed as agreed, and if not, who is responsible for this mismatch – or why the out-of-specification situation has been accepted. Regardless of the refit you are considering, always keep in mind what you wish to achieve and how you wish to have it measured. This is the only way to reach the finish line while achieving all your goals.

Written by Colin Mason, Technical Manager CCS

Colin has a university degree in Applied Chemistry. He has 30 years of expertise in yacht coatings project management, quality control of paint teams and training of inexperienced/learner painters. He is experienced in all aspects of superyacht coating i.e. topcoat spraying, filler application, tank coating, interior coating etc. and specialised in polymers. Furthermore, Colin has worked for mayor superyacht builders around the world.

Would you like to learn more? Go to www.ccsyacht.com or call the CCS office on +31 7512150

Would you like to learn more? Go to www.ccsyacht.com or call the CCS office on +31 7512150

Stay up-to-date with our articles and like our

Linked In Page https://www.linkedin.com/in/ccsyacht/